Washington Slagbaai Park Restoration

When grazing stops, the land starts breathing

Hike through the park today and you’ll see signs of change. Between sunbaked rocks, young shrubs push through the soil. Patches of green break up the dust. This is where recovery begins — in places where goats no longer graze.

Since 2019, thousands of free-roaming goats have been removed. The park is divided into zones, each one closed, cleared of grazers, and left to rest. It’s a careful approach, guided by both local knowledge and science.

Why the goats had to go

On Bonaire, an estimated 32,000 goats wander freely. In the park, they eat everything down to the roots — no young trees, no flowers, no shade. Just bare ground and drifting soil.

Left unchecked, the island’s oldest national park would lose its resilience. Erosion would strip the land, biodiversity would fade, and each rainy season would wash more of it away.

How recovery happens here

Each zone is fenced off for a time. Rangers track and remove goats using proven methods: capture pens, targeted culling, and GPS-collared “Judas goats” to locate the rest.

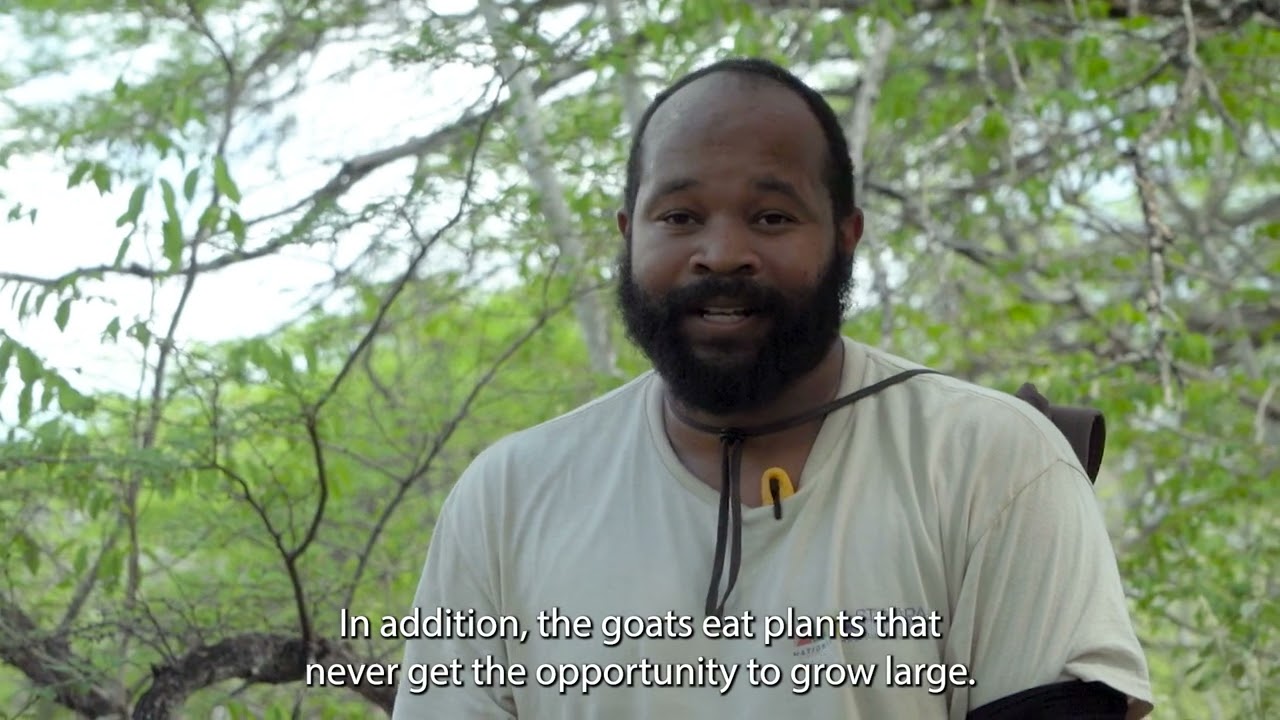

“You notice the difference right away,” says one ranger. “Where it was dry and bare for years, I’m seeing young shrubs again.” Already, soil holds more water, seeds sprout, and insects return. The land does the rest when we give it the chance.

Signs of a comeback

Vegetation is returning. Roots hold the soil in place. Birds, lizards, and pollinators are finding food and shelter again. And what works here can work elsewhere: Washington Slagbaai is becoming a living classroom for restoring nature across Bonaire.